A number of scientists who have actually been working with sea ice measurement had predicted some years ago that the retreat of Arctic summer sea ice would accelerate as it is part of a fundamental change. The same applies to the land ice masses like the Greenlandic ice sheet.

Greenland – the Ice Age Island

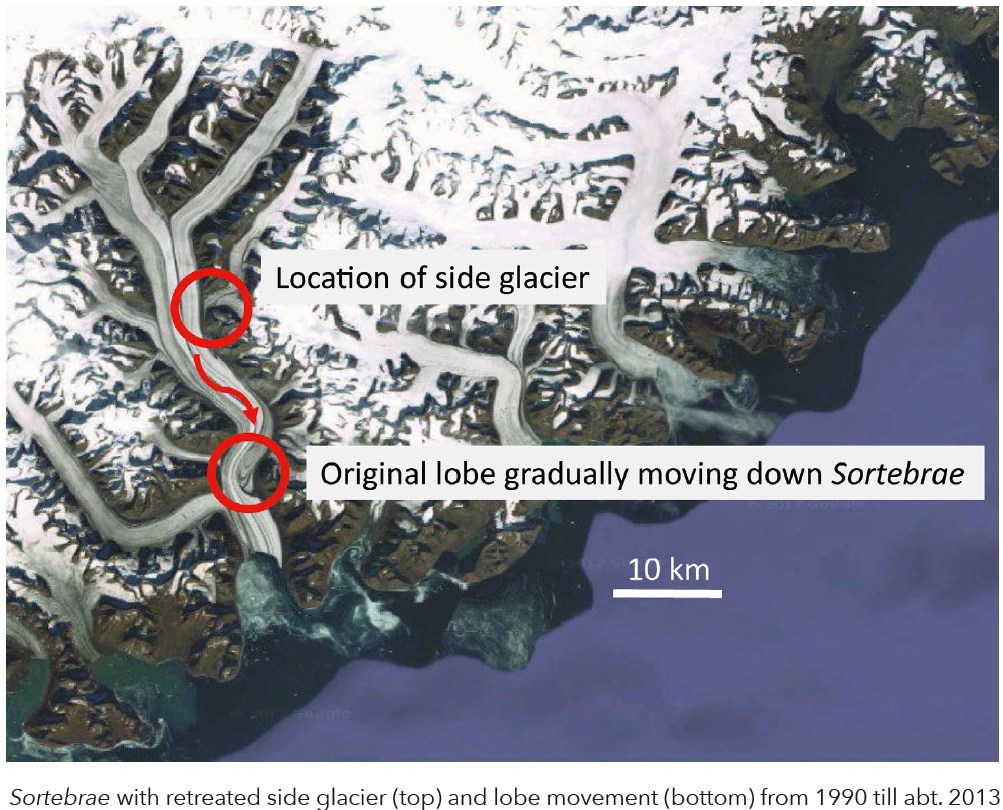

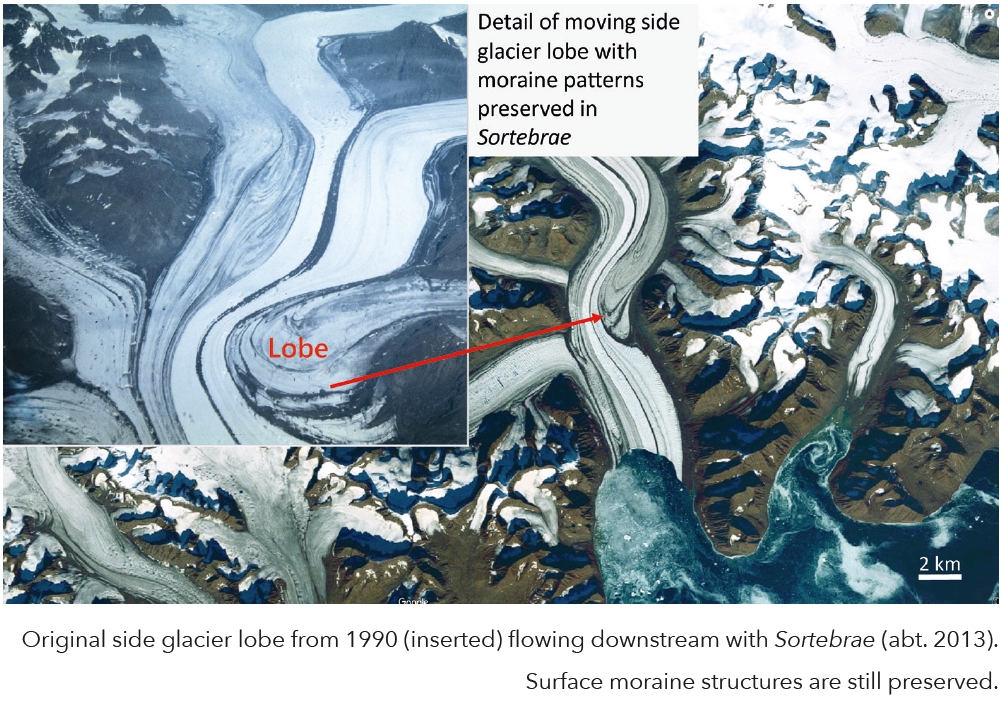

On the 12th July 2012 NASA reported that Greenland’s inland ice was melting that day on its highest peaks at 3.000 m asl. This has never been observed since the launch of Cryosat satellites, and was a consequence of global warming. From a plane I spotted in 1990 a mighty glacier flowing towards East Greenland’s Blosseville Kyst, which prompted me to take a photo, because it reminded me of an elephant foot which reached deep into the main glacier deforming it due to enormous ice pressure. 20 years later this view would pop up in my life again: in the age of Google Maps I searched for that glacier and was able to locate Sortebrae high in the Frozen Latitudes. The elephant foot had disappeared on the satellite image dating from around 2013. However, looking closer, I got excited when I discovered the side glacier’s tongue about 20 km further downstream. It still showed its original shape including the moraine patterns, but was heavily distorted by the strong forces of the flowing ice. This shape has been there since the 1990’s and is now less than 8 km away from breaking off into the East Greenland Sea. It took about 20 years to move 20 km downstream, so it might be completely gone by 2025.

Our route through the interior of Nuugssuaq took us to the places where our souls had already destined us to go to experience Frozen Morphs: tundra surfaces covered with deep and soft moss – exhausting for hikers; wide valleys bordered by frost scree, which has eroded over centuries by the forces of cryogenesis from the granite and gneiss mountains into sharp edged, fragile boulders, which moved into a new, more stable position under our feet; rivers that froze our legs until we were able to revive them on the other side; extensive snowfields covered by blood snow – Chlamydomonas nivalis, a reddish, cold-loving lichen; the inland ice, bound by vertical ice walls 50 m high, with raging rivers and waterfalls tumbling down; herds of reindeer wandering over lush lichen cushions and permafrost polygons, thawing and wobbling like jelly under our mattresses at night set off by our body heat, resembling the warming processes which are currently experienced throughout the Arctic. However, these frost polygons were often the only suitable places for our tents in a frost bitten rocky landscape. The hills of Nuugssuaq, the ice lakes, and the vast valleys dotted with melt water lakes were awe inspiring. On one of the many plateaus we crossed on our way through the interior of Nuugssuaq, we had to cut steps with ice axes into the snow walls of a river bed, where we found Nailed Ice, which only develops under certain climatological conditions. The weather was kind to us, with many sunny days, little rain and moderate temperatures between 0°C and +15°C. At the end, when we thought we had navigated the wildest parts of the interior of Nuugssuaq, we encountered a landslide not recorded on the map, which deprived us of all our remaining energy and became a real impediment on our way to Saqqaq. Boulders the size of houses lay loosely on top of each other with deep crevasses threatening to devour us and challenging our navigation skills constantly.

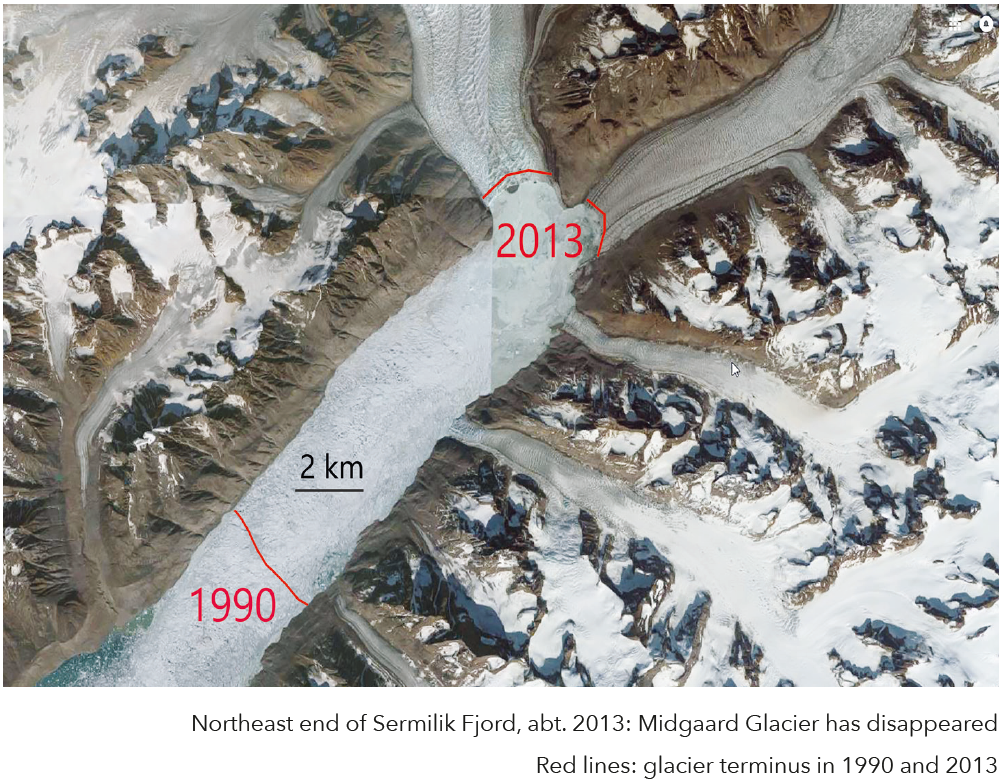

At the East coast of Greenland, we stumbled into quick sand, which tried to suck us into its cold depths, but luckily only pulled off our Wellingtons. Helping each other we found a way through the sand labyrinth to the other bank. We could not reach the calving front of the incredibly long Midgaard glacier – the glacier comes through a valley labyrinth from the inland ice 70 km away, but had retreated by about 15 km from where it should have been according to our map, which was based on glaciological data from the late 1930’s. This corresponds to about 400 m per year along a width of 5 km! Judging from Google Maps, the glacier has retreated since then a further 15 km in half the time. The outlet glacier has melted very fast and what was formerly known as Midgaard glacier has disappeared completely! The two main glaciers which merged in 1990 to become a single glacier now end separately in the innermost Sermilik fjord. We were not aware that our photos captured glacier levels which are unlikely to be seen in the coming centuries. I climbed a foothill to enable me to see over Midgaard glacier and got glimpses into the Schweizerland and the massive lateral moraines which transformed the edge of the fjord into insurmountable terrain. Frozen Morphs of Arctic morphology!

Franz Josef Land – the Very End of the World

The journey began long time ago in my head because, in my dreams, the calm waters of the wide sounds between the islands were projected into my mind. The smooth, glassy water surface mirrored the islands perfectly in an Arctic summer night. These dreams were so real that many weeks later I thought I could recognize the places, even though I had never seen them before. My head had produced the right climate

to fit the hundreds of islands of the archipelago, completely covered by snow, glaciers and enormous ice caps right at the end of the Arctic summer – true Frozen Morphs. In the middle of the night, at the end of August, at 82 degrees north, the sun rose at the northern end of the archipelago still a few degrees above the Arctic Ocean. However, the climate in my head indicated that the real-life climate in the first quarter

of the 21st century in the Frozen Latitudes had already warmed up by a few degrees more than in lower latitudes: no pack ice covered the many sounds such as the Austrian Channel, the British Channel, Markham Sound, the Collinson Channel, only glassy water surfaces. The ship steered through the constant fog that hung in large and small swathes over the mountains. Sometimes there was nothing to see except the hand in front of the eyes. Sometimes sunbeams broke through the lead-lavender-grey sky to highlight icebergs, scars under ice caps and frost rubble covered with fresh snow. An intangible humility was in this unspoilt Pure Landscape at the true end of the world. The horizon is dominated by ice cliffs which drop vertically into the sea to eventually disintegrate into huge icebergs. They arise in natural lines from the bare permafrost ground and continue all along to the horizon – fifty metres high and higher – until they are swallowed by earth’s curvature or by the everlasting mist.

In 2012, we became eyewitnesses of the lowest summer ice cover measured since 1979, when permanent observations of the pack ice using satellites had begun. Meanwhile, the daily updated ice maps can be accessed on the Internet, allowing everyone to get a picture of the dramatic ice loss of the last 30 years: In winter, the ice covers about 14 million km² around the North Pole, shrinking in summer to about 8

million km² – the breathing of the Frozen Latitudes – 2012 was the first time the ice was reduced to only 3.5 million km². That corresponds to a decrease of 50 %! At less than 1 million km², the polar sea will be considered ice-free. Even worse is the volume reduction, as there is less and less of thick multi-year ice, which storms can easily break up. In 2012, there was 80 % less volume compared to the long-term average since 1979, allowing us to sail without significant obstructions up to 83 degrees northern latitude.

The High Arctic Frozen Latitudes involuntarily invoke the feeling of gratitude and modesty – for being allowed to experience a piece of land – still nearly untouched by humans, coupled with the insight that restraint is necessary for the survival of mankind.

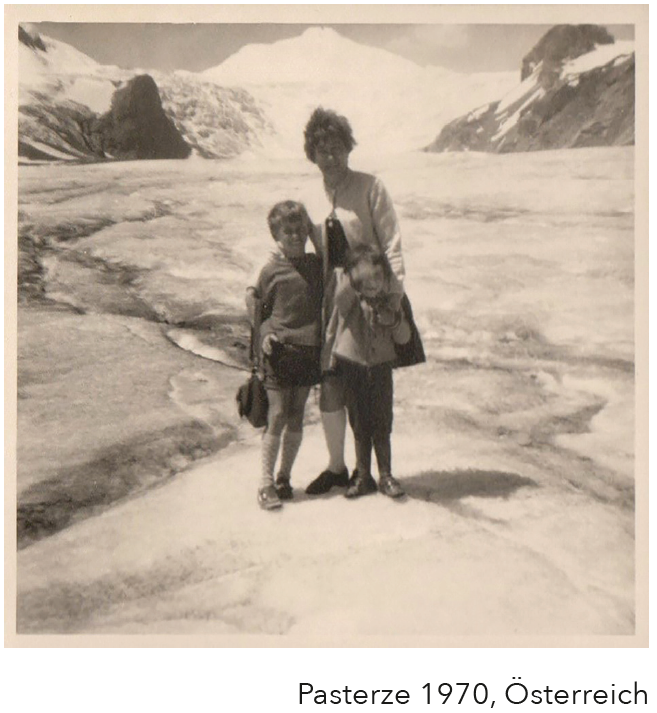

My enthusiasm for the cryosphere dates back to my childhood. At the age of 7, as any proper Austrian should, I went up the Alps via the “Großglockner Hochalpenstraße” with my parents and my brother. From a child’s perspective, we were exposed to daring adventures and dangers: right beside the narrow road, steep valleys seemed to pull us down to certain death; we saw overloaded cars and drivers who were anxiously looking at the steam coming out of their engines; we walked on the Pasterze, the largest glacier of the eastern Alps, where ice cold air was blowing under our Lederhosen and Dirndl. At the upper part of the 8 km long glacier we spotted the frightening crevasse system Hufeisenbruch where masses of ice tumbled down from the highest 3000 m peaks.

In 2014, when I travelled the same route with my wife in search of childhood memories, the Pasterze had shrunk into a dirty piece of ice covered by large amounts of debris and the Hufeisenbruch was a naked rock face. The past centuries caused a fundamental change which led to the death of even the largest Alpine glaciers and as described in FROZEN LATITUDES impacts the whole cryosphere up into the Highest Arctic. A fundamental change is happening.